To say Charlton Athletic have been through the wringer in recent years would be an understatement.

Ever since dropping out of Premier League 18 years ago they have suffered five changes of ownership, constant turmoil on and off the pitch, and 11 total years languishing in League One.

Or, in other words, a rollercoaster ride worthy of prime billing at Thorpe Park – and one which largely consists of Saw’s infamous hundred-foot drop.

According to Heather McKinlay, chair of the Charlton Athletic Supporters Trust (CAST), things got so bad “the club very nearly went under.”

But now, they are back in the second tier and appear to be a team on the rise once again.

After gaining promotion last season, they have started this one well by taking 23 points from their opening 18 games to sit six points off the Championship play-offs.

McKinlay said: “[For the first time in several years] all the building blocks are coming together.

“We’re back to everyone pulling in the same direction.”

So how did they get here?

Well, the story begins in the 2006/07 season.

After seven consecutive years in the top flight, the club suffered relegation as they struggled to adapt following the departure of long-serving manager Alan Curbishley.

A proposed takeover by an Abu Dhabi-based outfit in 2008 fell through, and the Addicks had to sell much of their squad to keep HMRC’s wolves from the door.

Following relegation to League One in 2009, Michael Slater and Tony Jiminez took over the next year – or so it seemed anyway.

In reality, the actual owner was London property developer Kevin Cash, who funded the club from the shadows whilst using Slater and Jiminez as the public face of his regime.

Despite the bizarre setup, Charlton enjoyed a period of relative calm for the first two years of Cash’s reign.

Chris Powell rebuilt the side well following that calamitous 2008/09 campaign, and led them to a monstrous 101-point promotion from League One three years later.

But Charlton being Charlton, choppy waters were always going to return eventually.

Following promotion, Cash allegedly decided to stop funding the club, under an apparent belief they would be able to break even in the Championship.

Unlike The Script, however, they couldn’t do so and financial woes once again began to mount up.

The Addicks limped along for a season and a half until Roland Duchatelet’s arrival in 2014, and under him they would enter their stormiest period since narrowly escaping liquidation in the 1980s.

The Roland Duchatelet years: calamity, chaos and constant turmoil

The Belgian businessman bought the south east Londoners for £14m, hoping to integrate them into a multi-club ownership model which included the likes of Standard Liege and Carl-Zeiss Jena.

It goes without saying, things didn’t work out.

The beloved Powell was sacked despite his success due to disagreements with the new board, and later claimed interference from Duchatelet in tactics, transfers and team selection.

Speaking to the Charlton Athletic Supporters Trust in 2015, he said: “I’d be in my office and there’s a player turning up downstairs with his suitcase, saying he’s come to play.

“Who is it? It’s Loic Nego, it’s Anil Koç. I don’t even know who they are.”

A revolving door of managers followed, including Jose Riga (twice) Bob Peeters, Guy Luzon, and rookie Karel Fraeye.

Any young player with value – including future Premier League star Nick Pope – was sold off like a rare vase on Antiques Roadshow.

And to top it all off, Duchatelet even accused the fans of sowing disorder, claiming on Charlton’s website they “wanted the club to fail.”

McKinlay said: “He wasn’t a football fan, he isn’t a football fan.

“I think he thought he could prove everyone else wrong and show he could regularly make money from football, but the reality was much harder than he imagined.

“He put in people who weren’t experienced and didn’t understand English football.”

The East Street Investments era: new dawn to living nightmare

After years of fan protests against the fiercely unpopular Belgian, the Addicks were eventually sold to East Street Investments (ESI) in November 2019.

But far from being the dawn of a shining new era, their situation only worsened.

Initially, fans welcomed the takeover with open arms.

Matt Southall, the consortium’s chief executive, appeared to understand the necessity of keeping the Valley faithful onside.

And, of course, it helped that ESI weren’t Duchatelet.

But predictably, the situation escalated within months.

The first red flag was raised when it was discovered the club’s assets – including the stadium and training ground – hadn’t been bought from the Antwerp native.

This was, supposedly, a process which was due to be completed at a later date. But thanks to how quickly the consortium unravelled, it never materialised, and The Valley remains in Duchatelet’s hands.

Alarm bells really started ringing when a rift developed between Southall and majority shareholder Tahnoon Nimer, over accusations Southall was using club money to fund his lavish lifestyle.

He was sacked in March 2020 and this time, according to McKinlay, there really did appear to be no way back.

She said: “Everyone was excited when they (ESI) first announced they were taking over because we thought we got rid of Duchatelet.

“But it really was a case of out of the frying pan, into the furnace.

“By March 2020 it was all unravelling, and over the next few months we seriously feared for the future of the club.

“The football almost became a sideshow, it was whether or not we were actually going to have a club to support.”

The Thomas Sandgaard regime: Disarray, disorder, and overambition

Thomas Sandgaard purchased the club less than a year later, and at the very least he had good intentions.

Although he didn’t buy back The Valley and training ground from Duchatelet, he did secure long-term lease agreements with the former chairman.

And he genuinely tried to understand the concerns of supporters.

But like so many League One owners before him, his ambition wasn’t matched by his means – nor was it feasible for a club in Charlton’s position.

Four managers were sacked in under two years in the fruitless pursuit of a Premier League dream that never came close to materialising.

Effectively he was trying to win the Formula One World Driver’s Championship for Alpine, while driving an ageing Vauxhall Corsa with a faulty gearbox.

So chaotic was the Dane’s leadership that during his tenure, the club didn’t even have a permanent CEO and he appointed his own son to a key player recruitment role.

Global Football Partners and the road to recovery

Against such a tumultuous backdrop, the Addicks faithful would’ve been forgiven for not knowing what to expect when Global Football Partners bought the club in 2023.

And, indeed, the early signs suggested their regime would be another mess.

In an unpopular move, the well-liked Dean Holden was sacked for Michael Appleton, with what could charitably be described as less-than-positive results.

But eventually the new board got Nathan Jones at the third time of asking and, ever since, the green shoots of growth have started to appear again.

McKinlay said: “GFP’s goal is to build the club back up to be successful, which is aligned with what the fans want.

“They plan ahead, they have different scenarios, they are willing to put more money into the transfer window to make a success of the club and the crowds are returning.”

Truth be told, Charlton probably aren’t going up this season.

Defeats to recently-relegated Southampton, as well as automatic promotion contenders Stoke City and runaway leaders Coventry City, indicate they don’t have the quality to maintain a sustained challenge yet.

And they are further hindered by a crippling injury crisis which has wiped out many of their first team regulars.

But even if they don’t achieve promotion this season – and assuming, of course, they manage to avoid the drop – the Addicks can be proud of what they have accomplished.

They have come through a living hell which would’ve doomed most other clubs, and for the first time in almost two decades fans can finally start to dream again.

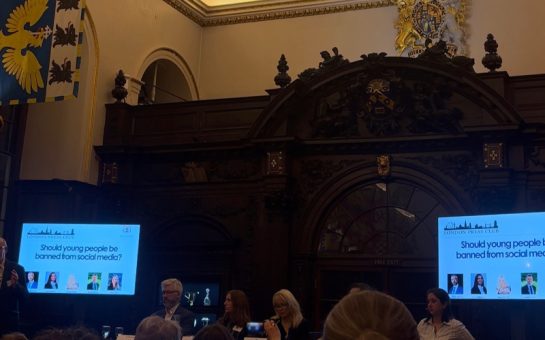

Feature image credit: CAST/Rhea Spencer-Newell

Join the discussion